Just ahead of the 2025 NBA Draft, Adidas officially signed both VJ Edgecombe and Jeremiah Fears to the roster, adding a duo of explosive guards that project to be two of the most exciting prospects in the entire class.

Each of the high risers and talented playmakers was taken in the lottery, with Edgecombe selected third by Philadelphia and Fears taken seventh by New Orleans. With both the 76ers and Pelicans betting big on each young gun, the duo will continue to take the next step in their pro path as they begin their Summer League play.

If they hoop as expected on the court throughout their rookie seasons, Adidas has already shown a willingness to build a sudden marketing push around each player. Both players took note of how The Three Stripes fast tracked its push around Damian Lillard and Anthony Edwards in the last decade, after each player took the league by storm in their first two seasons.

“For them to put their brand in someone so young’s hands, it’s knowing my opportunity could be there very soon, if I continue to do what I gotta do and take care of business,” said Fears. “Being able to see Ant take on that role and become the face of the Three Stripe Life is dope.”

With the 23-year-old “Ant Man” having already successfully launched his first signature shoe, the duo next up is hoping to make a similar impact with the brand.

“He solidified himself and built that fanbase, where everyone would want to wear his shoes,” added Edgecombe. “They want to jump like Ant or play like Ant. I feel like I have similar characteristics to that.”

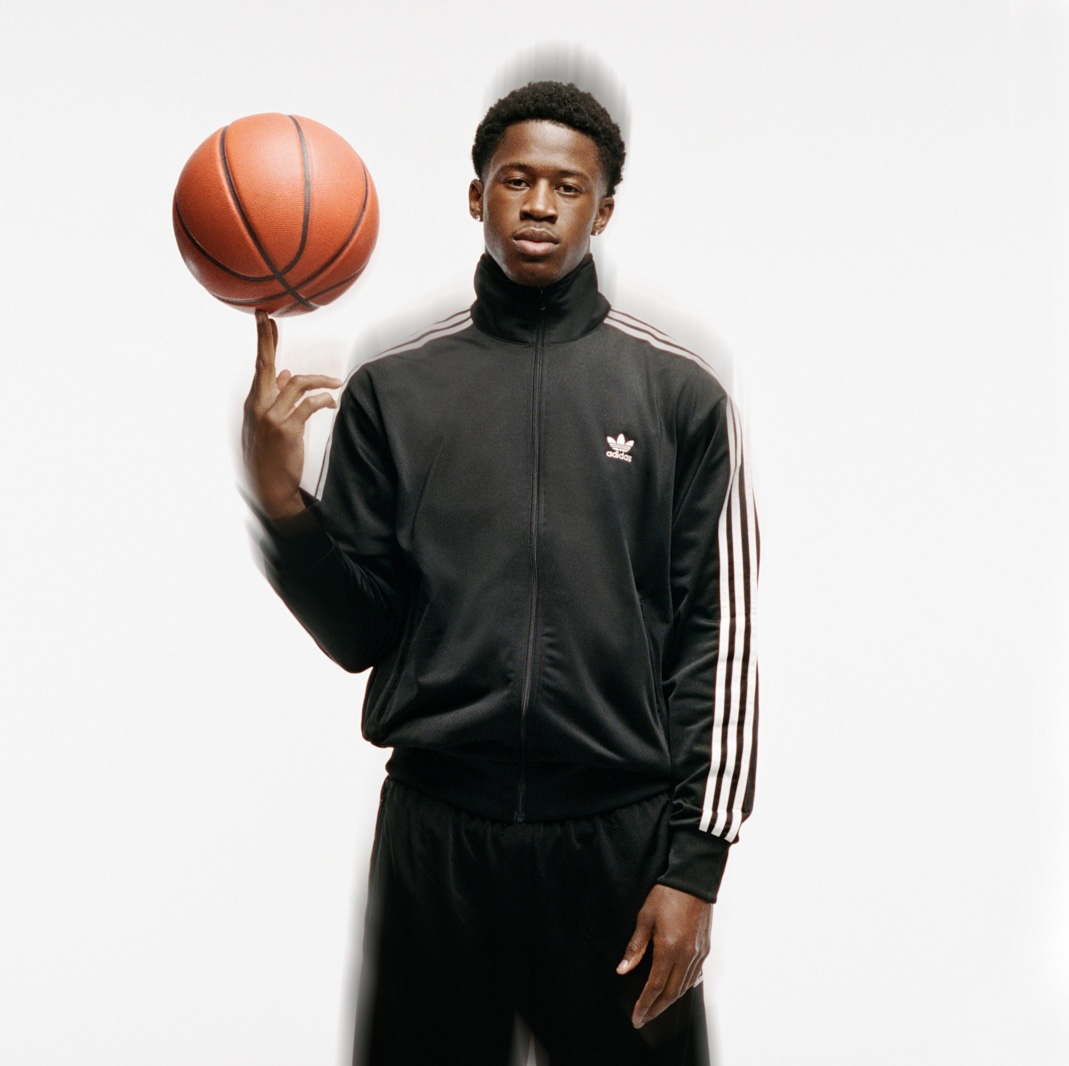

We recently got up with both VJ and Jeremiah at the Adidas showroom in New York, to hear more about the biggest factors that went into signing with The Three Stripes.

Three Keys for VJ ///

For Edgecombe — who played on the Adidas AAU circuit heading into his senior year of high school and blew up at Adidas EuroCamp in Italy to kick off the 2023 summer — the brand has been right there all along for his upward trajectory through the prep ranks.

These were the key factors that led VJ to The Three Stripes:

Impact in the Bahamas

It’s one thing to sign with a brand as an ambassador and help headline statement sneakers on the pro level. It’s another to work together out the gate to plan out a series of activations and givebacks to impact the region that made you.

As his Adidas deal was being finalized during the early spring, Edgecombe knew he wanted to give back in the Bahamas off top. In April, he held a basketball camp for 50 kids in his hometown of Bimini, where he also officially declared for the NBA Draft. Each happy camper was given a pair of the latest AdiZero hoop shoe and a branded shirt that simply read: “Bimini To The World”

“It was great, because growing up, I didn’t have that,” Edgecombe beamed. “I just want to be that role model for the younger kids back home, just knowing how hard it is sometimes. Not everyone is fortunate enough to be able to go and buy a pair of shoes, so I wanted to give back.”

Having already played on the Bahamas national team throughout international competition, and even weaving the vivid blue and yellow national color accents into his Draft night suit sleeves, Edgecombe is proud to carry his Bahamas heritage with him on his basketball journey and continue to champion the foundational traits he learned back home.

“Staying disciplined and staying true to who you are. Staying humble is something that I learned as time went on,” he described. “You ain’t going to just get recruited for D1 out of the Bahamas. The basic principles that I was taught by my mom, my grandma and my different role models have helped me. I’m going to try to do as much as I can.”

The Dame Effect

Everyone has a NBA star they look up to, and for Edgecombe, his hoop idol was playing across the continent in Portland.

“Growing up, Dame was my favorite player. I used to rock his shoes and thought I was Dame, to be honest,” laughs VJ, as he motions a well-practiced “Dame Time” wrist tap.

Watching the Adidas lifetime-deal-holding Lillard from afar, Edgecombe got accustomed to the Dame signature series of sneakers while emulating the explosive Top 75 scoring guard.

“Going into my senior year was the first time I played on the Adidas circuit. I went out there and did what I expected, and I opened some eyes,” he reflects. “I used to always wear Damian Lillard’s shoes. I had the Dame 3, 4, 5 and 6. I had all of them!”

As he rose the ranks in High School, Edgecombe was even invited to Lillard’s “Formula Zero” camp, a hands-on series of skills sessions that also focuses on the integrity, the commitment, and the mindset that it takes to make a pro.

“Dame is a great person — super humble and down to earth,” continued Edgecombe. “He can have a ego, but he doesn’t, because of who he is.”

Edgecombe went on to be named Formula Zero Elite Camp MVP by the end of that summer session in 2024. As the two continued to develop a relationship after the Formula Zero camp, VJ thinks back to how Lillard continued to reach out and check in, even in times that he was looking for guidance and support.

“After my first game in college, I had a bad game,” recalls Edgecombe. “He hit me and said, ‘You’re going to get in the flow of the game.’ He was giving me advice and telling me how in basketball, you’re going to have bad games, but you can’t let that affect the rest of your time.”

As Edgecombe begins his rookie season in Philly, he plans to wear a variety of sneakers to highlight all of the latest designs and innovations from the brand. He’ll also definitely be wearing the new Dame 10, bringing his sneaker rotation full circle and highlighting his favorite players’ signature series on the biggest stage.

Building With Family

Thanks to the relationship he had built with the folks behind the scenes at the brand over the last few years, that familiarity added to the allure of officially partnering as a pro.

“I always had a feeling that I was going to sign with Adidas,” he says now. “Since I played AAU with them and went to EuroCamp, it just opened my eyes up to the brand and gave me a full perspective of what’s going on with the brand.”

The process for players to land their shoe deal is entirely different now in the NIL landscape. Rather than wait til the spring just weeks before the Draft, Edgecombe had been having ongoing talks with several brands that expressed interest over the last year.

He wanted to take his time with the shoe deal, and instead signed major deals with the likes of Panini and PSD Underwear during his freshman season at Baylor.

Rather than pocket all of his NIL money, he created a scholarship fund at Gateway Christian Academy in his hometown, where he’ll cover the tuition, books and additional resources for at least three students each school year.

Edgecombe highlights how he’s already focused in on how to “invest and grow my money, instead of wasting it and spending it all,” all before he actually steps foot on the NBA hardwood for his regular season debut.

“I’m so happy that NIL came around while I was there in college,” Edgecombe beamed. “There’s definitely pros and cons, but there’s a lot of pros. It helped me take care of my family. It’s helped my mom and my little sister.”

As brands reached out last fall ahead of Edgecombe’s expected one-and-done season at Baylor, he leaned on the importance of family throughout his life, and the familiarity he already had with Adidas.

“When I signed, it was still during my freshman year in college,” revealed Edgecombe. “I said, ‘This is a family, and I’m going to keep doing whatever I can do within that to help grow the brand.’”

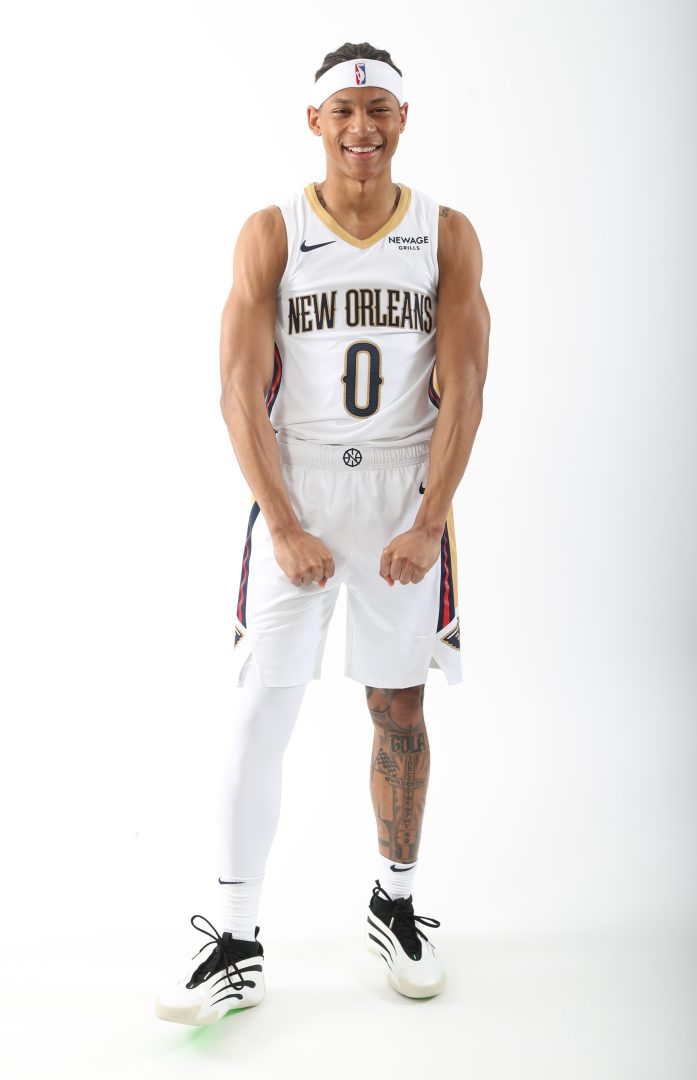

Three Keys for Jeremiah ///

Unbeknownst to Jeremiah Fears, just before he began his freshman season at Oklahoma, Adidas execs had tabbed him as one of their very favorite players in the entire 2025 Draft class that they hoped to sign.

As talks with his agents at LIFT Sports Management heated up this spring and he shot up the mock draft boards after his impressive single Sooner season, Fears was locked in on the vision that the brand saw ahead for him. He now credits a trio of key elements towards his signing with The Three Stripes:

Jeremiah 1s??

For both Edgecombe and Fears, the allure of breaking through as a pinnacle Adidas player proved to be a major factor.

“The relationship they have with their guys, and potentially having a signature shoe in the future was big,” Fears said.

While his game is relentless on the floor, Fears also points to a variety of other qualities he brings to the table that brands saw considerable appeal in.

“My mentality, being unique and my creativity,” he said. “I’m excited for the journey.”

As he landed deals like his major Adidas endorsement and a Tissot partnership ahead of the Draft, his understanding of the marketing world at just 18 years-old was already fast tracked thanks to the NIL landscape.

“It’s been dope, being able to experience everything before it’s time for the big leagues,” said Fears. “Being able to go through photoshoots, meet so many new people and build relationships — and being someone that brands know they can trust and market well — has been really cool for me.”

He’s been keeping tabs of the qualities that signature athletes at the highest level must have. How their top tier game is matched off the court by a presence that carries them into touchpoints of fashion, music and culture beyond just hoops.

“The swag is a little different,” he adds. “How you carry yourself and how you can promote it on a big stage.”

As Fears dreams of his own low-top signature silhouette in the years ahead, he’s mindful of the work that’ll he’ll have to put in towards building up his brand and his standing in the sneaker game.

“Eventually, you want to have little kids looking up to you,” he continued. “That want to go get the Jeremiah 1s.”

The DRose Effect

Growing up less than an hour outside of Chicago, a young Jeremiah soon had a childhood idol to follow as he was in elementary school. He loved how the Bulls’ homegrown #1 pick and franchise player hooped.

When Derrick Rose exploded through traffic and attacked the lane with an arsenal of finishes and floaters, he was showcasing where the new era of scoring point guards was headed. The future generation in Fears was following.

As DRose headlined his own Adidas signature series and put on for the brand, Fears couldn’t help but notice, and be inspired.

“Being able to get Derrick Rose’s first pair of basketball shoes, I wore those for a long time,” he says now. “Playing on his AAU team as well, was my earliest memory of picking up more Three Stripes shoes. I was on his team in the 6th grade. We ended up going to Alabama for a Big Time Tournament on the Adidas Gauntlet and that was dope.”

Fears works out before the Draft with Pro Hoops Inc. in the Harden Vol. 9. (Courtesy @highlights.from.heaven & @ProHoopsInc)

Starting out with a love for Rose’s line, Fears began to keep an eye on all of the key Adidas guards that followed.

“Ant Man, Dame Lillard and James Harden, I’ve loved all of their kicks,” Fears says, thinking back through the last decade of Three Stripes staples.

As he takes his own step into the pro stage, he’ll soon be facing off against each of the players he looked up to during his prep career. He now officially feels a shared Adidas connection with his fellow endorsers, as one of the brand’s next up-and-coming guards.

“In the future, we’ll build that relationship,” said the 18 year-old. “When I play against them, I won’t wear their signature shoe against them though. But I’ll definitely show them a lot of love.”

For Fears, there’s still a line to draw as a competitor.

“It’s off limits, definitely,” he added, with a smile. “That would be a one up thing, and I don’t want nobody to have a one up on me. I won’t wear their shoes against them, but definitely when I’m playing against someone else.”

For his rookie season, look for Fears to help headline the new Dame X, along with a key rotation of sneakers from Anthony Edwards and James Harden’s lines.

“Three Stripes have been doing something special for awhile now,” continued Fears. “Being able to be join the team and join the wave is great. The Harden Vol 9s are great. I really enjoy the material on the shoe and the way the shoe is designed, it sticks out to me. The feel and comfort is amazing.”

Continuing To Grind

Over the years, Fears has found a few phrases that resonated and pushed him. Mantras that he rallied behind that have led him to already reaching some of his biggest dreams. Some he’s even tattooed along his left leg for inspiration.

“Dream Until Its Your Reality”

“Be Different”

“The Creator of My Own Destiny”

Even his #0 jersey selection went viral for its double meaning: “Zero Fears”

Since a young age, one phrase stuck out amongst them all. Just a 7th grader at the time, Fears was often training with fellow Chicago-area native and eventual pro DJ Steward, when he first heard of his charging tagline.

“I just asked him,” Fears says now. “‘Why do you say GOLA?’”

“Grind or Live Average,” Steward responded.

From that point on, he was locked in.

“I went home later that day, and I thought about it the whole time,” reflects Fears. “You can either grind and get the life that you want, or you can just continue to dream about it and talk about it, but not put any of the work in.”

Ever since that day, the newly-turned teenager has worked towards living out his dreams. He credits the phrase with powering him further, leading to his eventual path as a top selection in the NBA Draft and a hopeful future in the Association ahead.

“I have it tattooed on my leg, right underneath my knee cap,” he added.

As he continues to build with Adidas to begin his NBA career, he’s hoping to showcase his story through marketing, and highlight how that dedication and commitment can inspire others to grind towards their own dreams.

“I’ve just carried that with me every step of the way,” said Fears. “And throughout everything that I did.”